The “Fuck you!” Poetics of Nuttaphol Ma

Gelare Khoshgozaran

25May2016 . Contemtorary

I place my body in spaces where I find myself delicately balancing between the confines of the clocking in and the clocking out, the dreams of leaving and dreams of roots, the longing and not BE longing. Words overflow from these experiences. Like laughters and tears, they flow uncontrollably. I collect these tearful, at times, joyful words. I restore them into poetry. Poetry roots my artistic works ranging from performances to installations to sculptures.

I selected these lines from Nuttaphol Ma’s artist statement because, unlike many, he is profound and precise when discussing his work. Take for example, in 2011 in a durational performance entitled “Born By the River” he walked for five and a half days in Death Valley, CA carrying a boat he had built after a dream where he helped a group of people carrying his body in a boat washed ashore. For the duration of the walk he carried the boat he had built from the lowest altitude in the United States, Badwater Basin to one of the highest, Whitney Portal, CA.

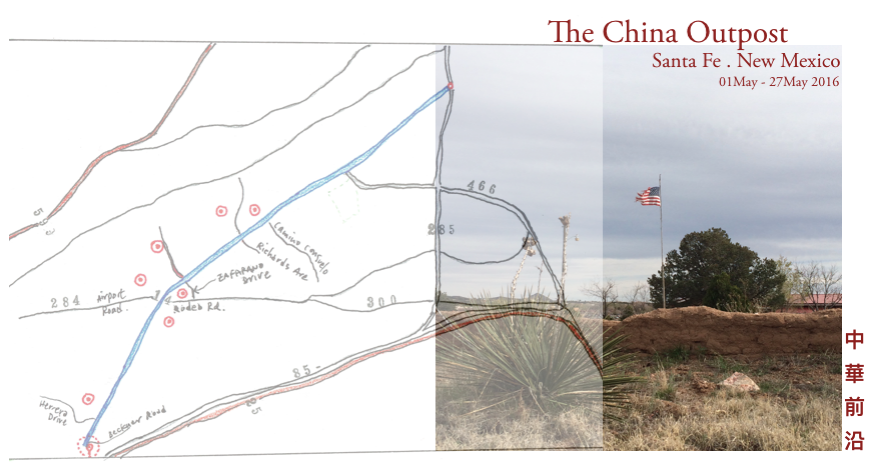

I visit Nuttaphol in a big Walmart parking lot on Cerillos Road in Santa Fe, NM. His project, The China Outpost–originally started in Los Angeles’s Chinatown in 2010–has moved to Santa Fe for the months of April and May that he’s been a resident at the Santa Fe Art Institute where I am also a current resident. According to the schedule on the artist’s website, each day he goes to the parking lot of a box store in Santa Fe, puts up his sign and works for hours in his self-imposed “sweatshop:” the back of his pickup truck.

The aim of the China Outpost is to rebuild the artist’s great grandfather’s house in the style of row houses in the U.S. but with the aesthetics of the original house located in a village in Southern China. From a Chinese immigrant family, born for three generations in Thailand, Nuttaphol migrated with his family to the United States at the age of seven. The idea of rebuilding his great grandfather’s house came to him when studying architectural conservation in Hong Kong where he had returned as an adult. His decision to “return” was informed by a racist childhood experience where his 5th grade teacher told him “to go back home!”. However, instead of using construction material to rebuild his great grandfather’s house, he accumulates plastic from recycled plastic bags collected from grocery stores in Los Angeles. In his “sweatshop,” I look at how he carefully shreds the bags into strands of five, ties the pieces together with identical knots and rolls them around a spool he has made after one that he had found at the Crate and Barrel store where he clocks in and outas a full-time employee.

As he pulls each strand of shredded plastic to straighten, he tells me he is “honoring” each part of it, he is “giving it soul.” Every day he returns to his “sweatshop” to continue the labor of “honoring” small pieces of the most despised material of the western liberal society: plastic, shred by shred, piece by piece. Everybody hates it, it’s bad for the environment, it stinks, it’s ugly, even banned in the stores in the city of Santa Fe. Stretching a strand between his hands, he holds it up in front of me and tells me “I hate this, this suffocates me. That’s why I shred it into pieces. The act of shredding the plastic bags to pieces, looping them into a thread, spinning them into a spool honor the mundane actions. These humble actions are also a meditation on the labor of adapting to a new home, on the repetitive unheroic actions of those who work within the confines of the clocking in and the clocking out. I work full-time in a retail job. I also work within those confines; however, being at The China Outpost, I clock in and I clock out under my own terms, not under that roof.” He points to the Walmart building at the end of the lot. Choosing plastic as the material to rebuild his great grandfather’s house was a decision not to “romanticize” the idea, according to the artist. Plastic is a material he is most familiar with, growing up with migrant parents who worked multiple low-wage jobs to support their family.

When we hear the word “sweatshop” we think of labor protests, inhumane labor conditions, lack of water, suicide. We can think of the Apple’s Foxconn employees, for example that were required to sign the ‘No Suicide’ pact. When I inquire about this word and the artist’s relationship to it he tells me “it is a way to draw awareness to a broad range of audiences and to jolt the imagery of working in an oppressed environment. Though I personally have not worked in such conditions, my entry to the use of the word draws from my experiences as an immigrant to this country. I recalled my mother’s silent cries at night the first months upon our arrival, when our family of five used to share one room. Her unspoken words rekindled our collective struggle as a family, our collective longing and not belonging. We all had multiple jobs, even me as a young child. After homework, dinner, the dishes, my sisters and I would head down to the garage where my mom sewed. She had bought a second hand industrial sewing machine and would receive weekly shipments of clothes parts from a manufacturer that outsourced the parts to her. The parts we received were sleeves and shoulders. My mom would sew those two parts together over and over again. I think we received a few cents per connection. Our job after dinner was to help my mom cut thread ends. Although these stories are far removed from the oppressed environments we imagine when hearing the word “sweatshop,” these memories are my closest connection to the word and that’s why I chose this word to describe The China Outpost, my self imposed sweatshop.”

The project is dreaming, and dreaming big. However, as dreamy as both the aim and the process may sound, they are deeply rooted in reality, a reality over which the artist has ownership: the reality of his life. The China Outpost is grounded in a narrative that subverts the typical, token migrant story that western liberal democracy desires to depict. It is subverting the utopic migrant narrative of coming to the “land of opportunities” where it only takes one hard working generation to turn plastic into gold; a myth rooted in the false promise of meritocracy in the same anti-plastic, liberal democracy that is founded on slavery, genocide, colonialism and the historic, ongoing (labor) exploitation of its unwealthy migrants.

The project is angry and stubborn, yet loving, poetic and delicate. It incorporates those qualities in its expressions, gestures and pace all thoughtfully controlled under the complete authority of the artist. Underlying the delicate poetics of the artist’s work lies a big “fuck you!” When the most basic liberal gesture is to hate plastic, and to be “aware” of its toxicity and harms, resistance becomes the labor of “honoring” plastic while accumulating it as building material, because for some of us it takes infinite laboring through one’s dreadful nightmares to fulfill a dream. Ma describes his labor as symbolic of “the labor of getting used to a new home.” He relives the affective labor of growing up as the child of working class migrant parents through his repetitive, physical labor of accumulating plastic, and the emotional labor of maintaining intimacy with this contested, most familiar, yet “choking” material to him. “The project is in semicolon phase” he tells me, making waves in the air with his hand. “And I KNOW that sitting here out in the parking lot I am under surveillance!”

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Gelare Khoshgozaran

25May2016 . Contemtorary

I place my body in spaces where I find myself delicately balancing between the confines of the clocking in and the clocking out, the dreams of leaving and dreams of roots, the longing and not BE longing. Words overflow from these experiences. Like laughters and tears, they flow uncontrollably. I collect these tearful, at times, joyful words. I restore them into poetry. Poetry roots my artistic works ranging from performances to installations to sculptures.

I selected these lines from Nuttaphol Ma’s artist statement because, unlike many, he is profound and precise when discussing his work. Take for example, in 2011 in a durational performance entitled “Born By the River” he walked for five and a half days in Death Valley, CA carrying a boat he had built after a dream where he helped a group of people carrying his body in a boat washed ashore. For the duration of the walk he carried the boat he had built from the lowest altitude in the United States, Badwater Basin to one of the highest, Whitney Portal, CA.

I visit Nuttaphol in a big Walmart parking lot on Cerillos Road in Santa Fe, NM. His project, The China Outpost–originally started in Los Angeles’s Chinatown in 2010–has moved to Santa Fe for the months of April and May that he’s been a resident at the Santa Fe Art Institute where I am also a current resident. According to the schedule on the artist’s website, each day he goes to the parking lot of a box store in Santa Fe, puts up his sign and works for hours in his self-imposed “sweatshop:” the back of his pickup truck.

The aim of the China Outpost is to rebuild the artist’s great grandfather’s house in the style of row houses in the U.S. but with the aesthetics of the original house located in a village in Southern China. From a Chinese immigrant family, born for three generations in Thailand, Nuttaphol migrated with his family to the United States at the age of seven. The idea of rebuilding his great grandfather’s house came to him when studying architectural conservation in Hong Kong where he had returned as an adult. His decision to “return” was informed by a racist childhood experience where his 5th grade teacher told him “to go back home!”. However, instead of using construction material to rebuild his great grandfather’s house, he accumulates plastic from recycled plastic bags collected from grocery stores in Los Angeles. In his “sweatshop,” I look at how he carefully shreds the bags into strands of five, ties the pieces together with identical knots and rolls them around a spool he has made after one that he had found at the Crate and Barrel store where he clocks in and outas a full-time employee.

As he pulls each strand of shredded plastic to straighten, he tells me he is “honoring” each part of it, he is “giving it soul.” Every day he returns to his “sweatshop” to continue the labor of “honoring” small pieces of the most despised material of the western liberal society: plastic, shred by shred, piece by piece. Everybody hates it, it’s bad for the environment, it stinks, it’s ugly, even banned in the stores in the city of Santa Fe. Stretching a strand between his hands, he holds it up in front of me and tells me “I hate this, this suffocates me. That’s why I shred it into pieces. The act of shredding the plastic bags to pieces, looping them into a thread, spinning them into a spool honor the mundane actions. These humble actions are also a meditation on the labor of adapting to a new home, on the repetitive unheroic actions of those who work within the confines of the clocking in and the clocking out. I work full-time in a retail job. I also work within those confines; however, being at The China Outpost, I clock in and I clock out under my own terms, not under that roof.” He points to the Walmart building at the end of the lot. Choosing plastic as the material to rebuild his great grandfather’s house was a decision not to “romanticize” the idea, according to the artist. Plastic is a material he is most familiar with, growing up with migrant parents who worked multiple low-wage jobs to support their family.

When we hear the word “sweatshop” we think of labor protests, inhumane labor conditions, lack of water, suicide. We can think of the Apple’s Foxconn employees, for example that were required to sign the ‘No Suicide’ pact. When I inquire about this word and the artist’s relationship to it he tells me “it is a way to draw awareness to a broad range of audiences and to jolt the imagery of working in an oppressed environment. Though I personally have not worked in such conditions, my entry to the use of the word draws from my experiences as an immigrant to this country. I recalled my mother’s silent cries at night the first months upon our arrival, when our family of five used to share one room. Her unspoken words rekindled our collective struggle as a family, our collective longing and not belonging. We all had multiple jobs, even me as a young child. After homework, dinner, the dishes, my sisters and I would head down to the garage where my mom sewed. She had bought a second hand industrial sewing machine and would receive weekly shipments of clothes parts from a manufacturer that outsourced the parts to her. The parts we received were sleeves and shoulders. My mom would sew those two parts together over and over again. I think we received a few cents per connection. Our job after dinner was to help my mom cut thread ends. Although these stories are far removed from the oppressed environments we imagine when hearing the word “sweatshop,” these memories are my closest connection to the word and that’s why I chose this word to describe The China Outpost, my self imposed sweatshop.”

The project is dreaming, and dreaming big. However, as dreamy as both the aim and the process may sound, they are deeply rooted in reality, a reality over which the artist has ownership: the reality of his life. The China Outpost is grounded in a narrative that subverts the typical, token migrant story that western liberal democracy desires to depict. It is subverting the utopic migrant narrative of coming to the “land of opportunities” where it only takes one hard working generation to turn plastic into gold; a myth rooted in the false promise of meritocracy in the same anti-plastic, liberal democracy that is founded on slavery, genocide, colonialism and the historic, ongoing (labor) exploitation of its unwealthy migrants.

The project is angry and stubborn, yet loving, poetic and delicate. It incorporates those qualities in its expressions, gestures and pace all thoughtfully controlled under the complete authority of the artist. Underlying the delicate poetics of the artist’s work lies a big “fuck you!” When the most basic liberal gesture is to hate plastic, and to be “aware” of its toxicity and harms, resistance becomes the labor of “honoring” plastic while accumulating it as building material, because for some of us it takes infinite laboring through one’s dreadful nightmares to fulfill a dream. Ma describes his labor as symbolic of “the labor of getting used to a new home.” He relives the affective labor of growing up as the child of working class migrant parents through his repetitive, physical labor of accumulating plastic, and the emotional labor of maintaining intimacy with this contested, most familiar, yet “choking” material to him. “The project is in semicolon phase” he tells me, making waves in the air with his hand. “And I KNOW that sitting here out in the parking lot I am under surveillance!”