A River Runs Through It

Constance Mallinson

09 Jul 2011 . Times Quotidian

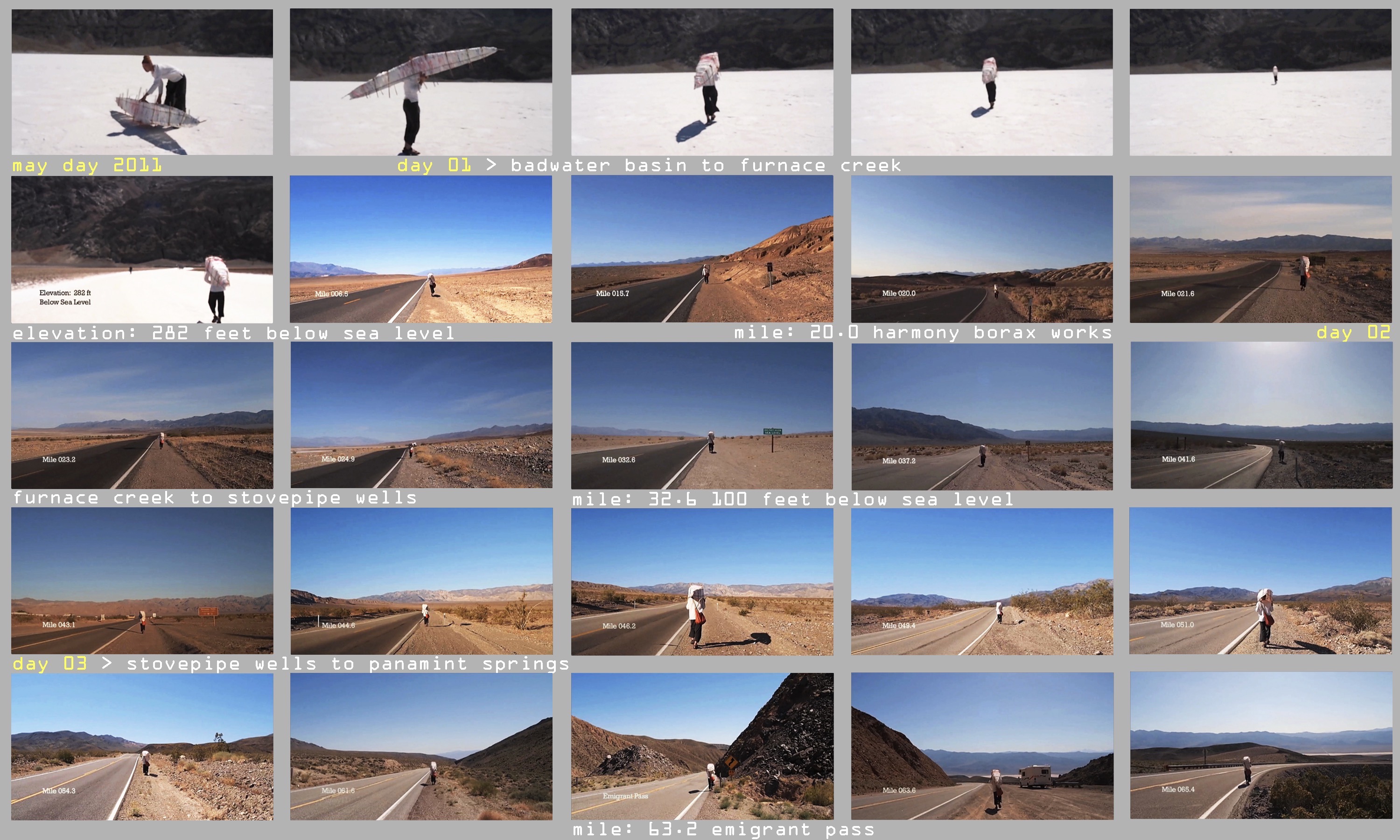

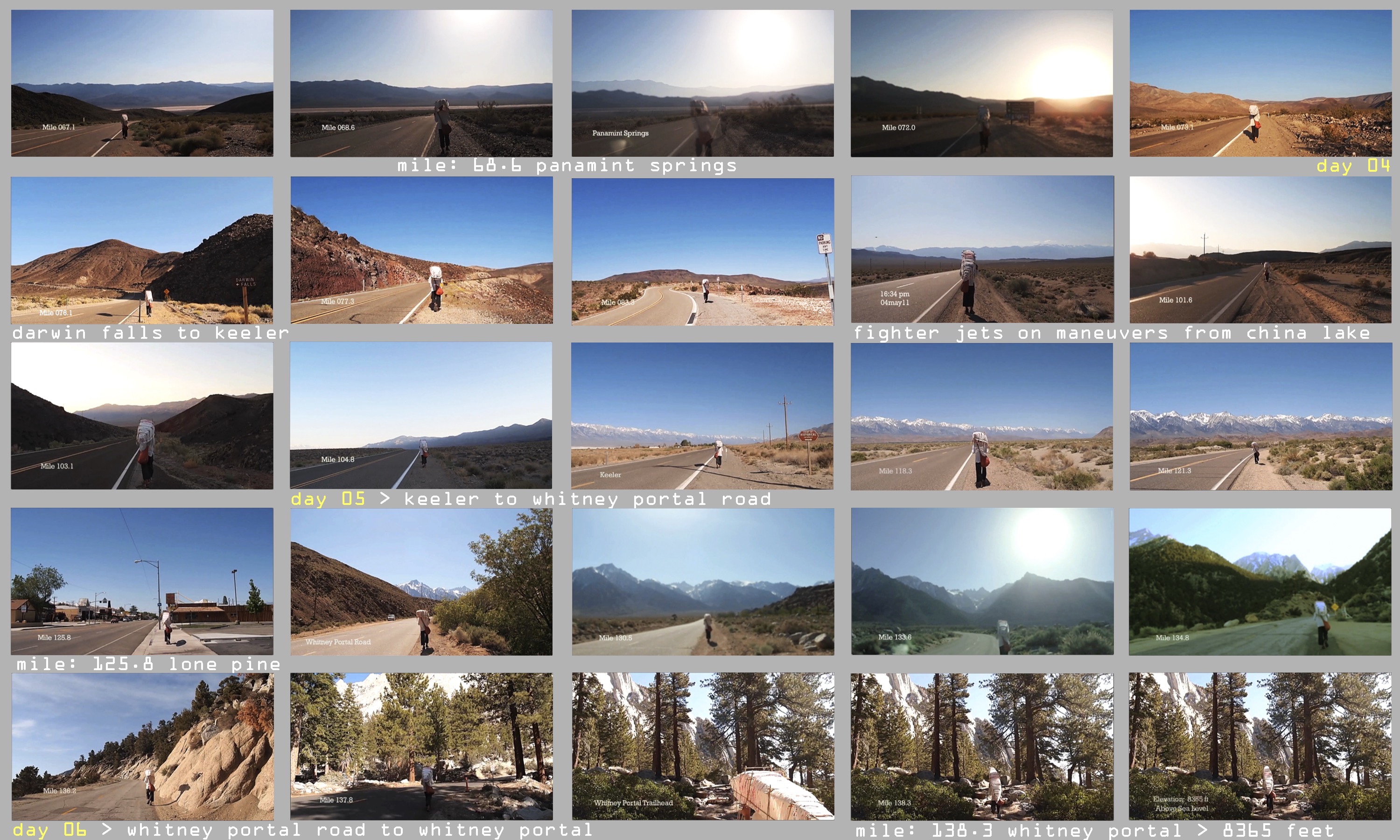

Badwater Basin in Death Valley, the lowest point in the continental US, is flat, empty, surrounded by desolate, desiccated mountains, and yet the near blinding whiteness of the valley floor symbolizes and enlarges upon the traditional ground zero for the artist—the vacant white studio wall. Or as Jean Baudrillard described the desert, it is the place of “superficial neutrality”, a “challenge to meaning and profundity.” Here on May Day this year Thai American multi-disciplinary artist Nuttaphol Ma began a 6 day, 138.3 mile documented performance/journey to the trailhead of Mt. Whitney—the highest point in the U.S.– carrying a body-sized lightweight handmade “boat” over his head. As recipient of the 2011 Feitelson Arts Fellowship, he has created a site-specific installation based on a prophetic dream and a lyric from the Sam Cooke song, A Change is Gonna Come at Barnsdall’s Los Angeles Municipal Gallery. Centered primarily on a two channel video of the walk shot by artist Victoria Tao, one video captures Ma walking on the highway away from the camera, the other depicts him walking towards it. The shoulder transported boat suggests a long and arduous sea voyage or the nomadic tent carrying life of Mongol tribespeople. Cars speed by intermittently and perilously close as the background scenery morphs from desert to foothills, to alpine forest. Perhaps the most arresting moment of the journey, however, is the sudden swift appearance of two fighter jets on maneuvers from China Lake Naval Base. They aggressively swoop low and loud from the sky, contrasting to the simple, rythmic naturalness of Ma’s footsteps, imposing their arrogant technology on the sublime ancient landscape. Because we never see Ma’s face or expression for it is concealed by the boat, because he continues walking in the presence of such naked power, the walk appears less like Ma’s ego driven personal struggle, but rather a gesture in communion with historic marches and heroic treks. By the time we see him reaching the portal to Mt. Whitney and the land boat is finally put down, there is a recollection of Gandhi’s march from Ahmedabad to coastal village of Dandi where he produced salt in protest against the British imposed salt tax, Martin Luther King’s Civil Rights marches, the universal immigrant seeking a better life against the restrictions of borders, threats of war and natural disasters.

As with his previous pieces like The Ruins of Daedalus’ Labyrinth seen at Pasadena’s Armory space in January 2011, Ma’s pieces are not easily categorized but are a kind of ecological mix encompassing sculpture, performance, video, and installation all inextricably bound with his current and past life, his dreams, spirituality, objects from mass culture/everyday life, and diverse sociopolitical, anthropological concerns. At Barnsdall, the two Born by the River videos are projected onto suspended diaphanous fabric walls, the “building blocks” of which are based on measurements taken from intervals in the gallery’s columns, and sewn from discarded fabric packaging collected from Crate and Barrel where he is a fulltime employee. The sewing takes place in Ma’s Chinatown “sweatshop” studio he describes as “a laboratory to translate critical thoughts” – a site for examining cultural phenomena, patterns, attitudes. Here in solidarity with the rich history of immigrant labor, he carefully joined the bags, stamping the rows of muslin rectangles with the dates of completion; the visible stitches seem to reiterate every step of the journey. The meticulously shaped and seamed sacks now create an unforetold relationship with their new space where they assume new life and connectedness with the city. In fact, Ma stated, “Everything is a semi-colon” with every object repurposed and continuously recycled in subsequent work and challenges the western notion of the discreet finished, museum-ready artwork. Adjacent to one wall atop a small tower of found plywood disks discarded from an art student’s project is a galvanized bucket with an attached poem by Ma. It holds measured hardware store paint sticks wound with skeins of “yarn” fabricated from the plastic shopping bags sewn and stretched over the bamboo frame and removed from the vessel he carried in the current video before it was burned at journey’s end. Before the bags formed the boat sides, they had been crocheted into a large hanging “fabric”. The bags also await their reincarnation into a future installation. Part of the haunting, evocative soundtrack for the video is taken from a skipping, repeating section on an old record of Tchaikovsky’s Pathetique Symphony interspersed with Tao’s violin compositions. The last symphony Tchaikovsky wrote before his suicide, the Pathetique is not an end for Tchaikovsky or this outmoded LP but is joined in a never ending chorus of consummate, melancholic beauty. The fabric bags made by anonymous Indian workers and almost discarded by the corporate store have become a commemorative wall underscoring the practices of our consumer culture willfully oblivious of the backbreaking work of factory slaves. Symbolically connecting the present with the past, a bell that is heard in the video soundtrack that has been used in earlier installations such as In the Red, a 2009 exhibition at Claremont Graduate Gallery in which Ma constructed his family’s original dwelling from floors of handmade pallets and suspended “walls” constructed from Chinese restaurant place mats recalling the ones used in the family restaurant when they were new arrivals to Los Angeles. In the center of the “house” sat a bowl over a power socket containing the bell ready to fill the space with its reverberations. This same bell is struck at the outset of Ma’s walk so that its vibrations would break and renew the space near the site where Chinese migrants toiled in the late 1800’s to clear way for the road used for the 20 mule team to transport borax across a rugged region called the Devil’s Golf Course.

Aside from the Buddhist reflection underlying Ma’s practice—universal love and compassion, divesting oneself of the ego-centered life and attachments to permanence or outcome (often embodied in contemporary western art), the exchange of love for pain and suffering in working out negative karma, concepts of rebirth, listening to dreams, “right” behavior and awareness to promote liberation and freedom to name just a few tenets—his work shares characteristics with a number of contemporary artists and trends in critical ideas. This work has its roots in the Fluxus Movement of the 1960’s when arch proponent Guy Debord espoused experimental participatory art events in order to disrupt and break the hold of capitalism. French curator and theoretician Nicholas Bourriaud has more recently specified a tendency he calls “Relational Aesthetics” in which artists work ”within the gaps of capitalism” in order to transgress traditional notions of property and ownership and to promote “a culture of activity to counteract market induced passivity.” Further for Bourriaud, “artistic activity is a game whose forms, patterns, and functions develop and evolve according to periods and social contexts; it is not an immutable essence.” Art then operates in the realm of human interactions, not as an “assertion of private symbolic space” but as a challenge to the hierarchies entrenched in corporatism or the state and the underlying violence of globalism. Whether Rirkrit Tiravanija who hands out free soup and curry to audiences, Gabriel Orozco who slung a hammock at MOMA, or Jens Hanning who broadcast humorous stories in Turkish to disenfranchised immigrants in Copenhagen, a number of contemporary artists are fomenting tiny revolutions that take place in the face of giant superstructures, creating micro-communities and models of sociability. Their practices undermine art as commerce, opting instead to put forth ideas about art that Bourriaud describes as “a state of encounter” and a denial of “the existence of any specific ‘place of art’ in favor of a forever unfinished discursiveness …the production of gestures wins out over the production of material things.” Similarly for Ma, “the doing part of the art is like making a meal, just a process.”

This kind of approach, then, necessitates downplaying artisanal craft and the usual process of exchange. For “relational” artists, if there could even be a “goal” it is to unbind the artwork, expanding its territories exponentially from pure visual pleasure, virtuosity, and limited historical readings such as “Modernism” and “Postmodernism” to integrate and interact freely with social, political, and cultural environments. Why would fine artists want to seek this position? Notwithstanding the contradictions and ironies of celebrity that accrue to artists like Tiravanija, few within the contemporary art/culture industries would deny that art has lost much of its transgressive shock value and that artists who continue to be motivated by models of alienation with hollow , spectacle driven work do so primarily as marketing strategies for financial gain. Critics like Suzi Gablik have argued that this constitutes a kind of endgame in which the avant garde epater la bourgeoisie is decadently rehashed in the hopes that that paradigm can continue to lead to fame and riches. She believes the world is in such a state of crisis that artists can use their talents and venues to promote and emphasize healing, reconciliation, and understanding by any means at their disposal without losing art’s sense of inventiveness, playful engagement, complexity, or suggestiveness. Or as Ted Purves explained in his book “What We Want is Free”, artists can examine what benefits they might bring to society through acts of generosity, exchange, and democracy. The audience becomes much more of a crucial player, a collaborator, again subverting the traditional nature and status of aesthetic endeavors.

When I first became acquainted with Ma in 2007 he told me of a performance where he carried dirt filled pillowcases labeled “Made in Pakistan”, purchased at Walmart, up and down a mountain near Los Angeles. Bringing into focus labor practices that support First World consumerism, the piece is unlikely to stop Americans from supporting exploitive labor in their buying habits, but addressed levels of awareness that can be transmitted by small individual acts. On a more ambitious scale, Ma’s next piece will involve a reconstruction of his grandfather’s home in China, packing the components in shipping containers, and if possible, residing in the containers as they leave the San Pedro docks to be eventually installed on site in China. As in Born by the Riverwhich both refers to the dream sequence that “birthed” the artwork and the never ending currents of water on the globe that carry people, give life and also take it away, the river will now figuratively flow into the Pacific to not only allow Ma to reenact ancient trips, but also begin anew. Ma’s studio will morph from a small Chinatown sweatshop to a crammed crate, suggesting that the studio is no longer a specialized isolated place to produce art, but involves a continuum of spaces, locations, and configurations. Quoting the 16th century Japanese poet Basho who wrote, “And the journey itself is home” Ma could have also remarked, “And my studio is never the same but also a journey.”

Aside from the Buddhist reflection underlying Ma’s practice—universal love and compassion, divesting oneself of the ego-centered life and attachments to permanence or outcome (often embodied in contemporary western art), the exchange of love for pain and suffering in working out negative karma, concepts of rebirth, listening to dreams, “right” behavior and awareness to promote liberation and freedom to name just a few tenets—his work shares characteristics with a number of contemporary artists and trends in critical ideas. This work has its roots in the Fluxus Movement of the 1960’s when arch proponent Guy Debord espoused experimental participatory art events in order to disrupt and break the hold of capitalism. French curator and theoretician Nicholas Bourriaud has more recently specified a tendency he calls “Relational Aesthetics” in which artists work ”within the gaps of capitalism” in order to transgress traditional notions of property and ownership and to promote “a culture of activity to counteract market induced passivity.” Further for Bourriaud, “artistic activity is a game whose forms, patterns, and functions develop and evolve according to periods and social contexts; it is not an immutable essence.” Art then operates in the realm of human interactions, not as an “assertion of private symbolic space” but as a challenge to the hierarchies entrenched in corporatism or the state and the underlying violence of globalism. Whether Rirkrit Tiravanija who hands out free soup and curry to audiences, Gabriel Orozco who slung a hammock at MOMA, or Jens Hanning who broadcast humorous stories in Turkish to disenfranchised immigrants in Copenhagen, a number of contemporary artists are fomenting tiny revolutions that take place in the face of giant superstructures, creating micro-communities and models of sociability. Their practices undermine art as commerce, opting instead to put forth ideas about art that Bourriaud describes as “a state of encounter” and a denial of “the existence of any specific ‘place of art’ in favor of a forever unfinished discursiveness …the production of gestures wins out over the production of material things.” Similarly for Ma, “the doing part of the art is like making a meal, just a process.”

This kind of approach, then, necessitates downplaying artisanal craft and the usual process of exchange. For “relational” artists, if there could even be a “goal” it is to unbind the artwork, expanding its territories exponentially from pure visual pleasure, virtuosity, and limited historical readings such as “Modernism” and “Postmodernism” to integrate and interact freely with social, political, and cultural environments. Why would fine artists want to seek this position? Notwithstanding the contradictions and ironies of celebrity that accrue to artists like Tiravanija, few within the contemporary art/culture industries would deny that art has lost much of its transgressive shock value and that artists who continue to be motivated by models of alienation with hollow , spectacle driven work do so primarily as marketing strategies for financial gain. Critics like Suzi Gablik have argued that this constitutes a kind of endgame in which the avant garde epater la bourgeoisie is decadently rehashed in the hopes that that paradigm can continue to lead to fame and riches. She believes the world is in such a state of crisis that artists can use their talents and venues to promote and emphasize healing, reconciliation, and understanding by any means at their disposal without losing art’s sense of inventiveness, playful engagement, complexity, or suggestiveness. Or as Ted Purves explained in his book “What We Want is Free”, artists can examine what benefits they might bring to society through acts of generosity, exchange, and democracy. The audience becomes much more of a crucial player, a collaborator, again subverting the traditional nature and status of aesthetic endeavors.

When I first became acquainted with Ma in 2007 he told me of a performance where he carried dirt filled pillowcases labeled “Made in Pakistan”, purchased at Walmart, up and down a mountain near Los Angeles. Bringing into focus labor practices that support First World consumerism, the piece is unlikely to stop Americans from supporting exploitive labor in their buying habits, but addressed levels of awareness that can be transmitted by small individual acts. On a more ambitious scale, Ma’s next piece will involve a reconstruction of his grandfather’s home in China, packing the components in shipping containers, and if possible, residing in the containers as they leave the San Pedro docks to be eventually installed on site in China. As in Born by the Riverwhich both refers to the dream sequence that “birthed” the artwork and the never ending currents of water on the globe that carry people, give life and also take it away, the river will now figuratively flow into the Pacific to not only allow Ma to reenact ancient trips, but also begin anew. Ma’s studio will morph from a small Chinatown sweatshop to a crammed crate, suggesting that the studio is no longer a specialized isolated place to produce art, but involves a continuum of spaces, locations, and configurations. Quoting the 16th century Japanese poet Basho who wrote, “And the journey itself is home” Ma could have also remarked, “And my studio is never the same but also a journey.”